Vasilis Kollaros: How the Hagia Sophia became a museum – The role of American historian Thomas Whittermore

01/07/2020

The conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans, in 1453, was the starting point for the conversion of Hagia Sophia into an Islamic mosque. For almost 500 years it functioned as a place of worship for Muslims before it was converted, in 1934, into a museum. But what prompted Mustafa Kemal to give his consent to this transformation? It is therefore of particular interest to see the background and ideological underpinnings of the decision of the last Gazi of Ottoman history to turn Hagia Sophia into a museum.

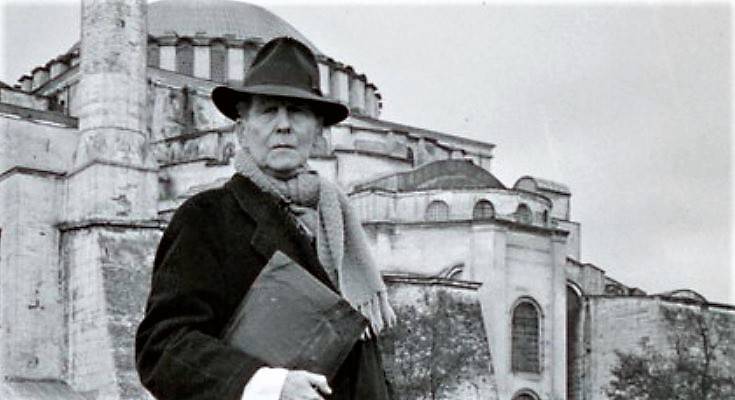

Based on some scholars of the history of Justinian’s work, the American Byzantine Institute, and in particular its founder and director, American archaeologist Thomas Whittemore (1871-1950), played a key role in transforming the Hagia Sophia into a museum. Whittemore maintained an excellent personal relationship with Kemal, while he had a strong network of acquaintances in American society, mainly people from politics and economics (Rockefeller Family).

In addition, some of them had funded the establishment of this institute, while they were particularly interested in Christian monuments. Another reason that prompted Kemal to allow works was the fact that the building complex of Hagia Sophia, in the mid-1930s, was in poor condition. As early as the middle of the 19th century, the period of Tanzimat reforms, some, non-crucial, maintenance work had begun around the main building complex.

The interior, however, had been untouched for a long time, with Christian mosaics covered in plaster, as Islam forbids depictions. Finally, in 1931, the American Byzantine Institute received permission from the Turkish government to proceed with the restoration and maintenance of the mosaics of Hagia Sophia.

Turkish expediencies – Everything is Turkish

Kemal’s consent to the conversion of Hagia Sophia into a museum was part of a more general policy of promoting the first Turkish Republic, as a state of a strictly secular nature, free from Ottoman heritage and religious divisions of the past.

Silently, however, Turkish identity continued to be defined in religious terms, with known results for those belonging to minority groups. The image of a time-worn imperial mosque did not go hand in hand with Kemal’s aspirations for the image of the new Turkey. The Ottoman building tradition was considered inappropriate and incompatible with the ideology and aesthetics of the new regime.

At the same time, the “new” state, therefore, needed “new” citizens. The main goal of the Kemalist leadership, after 1923, was the creation of Turkish citizens. Archaeology and history played an important role in this process, as the Turkish leadership needed to foster a “common story” that would create a sense of a single, always Turkish, nationality.

Statements by a Turkish education minister in the mid-1930s said: “All historical works in Turkey testify to the creativity and culture of the Turkish race, even if they are referred to as the works of the Hittites, Phrygians, Lydians, Romans, Byzantines or Ottomans. The name only specifies periods. Everything is Turkish, and therefore it is the duty of all Turks to maintain it. ”

This statement is representative of the Kemalist leadership’s way of thinking about how it perceived the historical value of the monuments within its territory. Turkism would be the melting pot of the previous civilizations that lived and worked in the geographical area of Kemal’s Turkey. In this context, Hagia Sophia, like the other historical monuments, had to lose its Byzantine and Ottoman heritage and adopt a new cultural role. In other words, to turn it into a place not reminiscent of a Byzantine church or mosque, but a place of remembrance.

On the agenda of the Turkish leadership

Internationally, Kemal’s decision reaffirmed, in the eyes of the West, the secular character of the first Turkish Republic and the attempt to modernize Turkish society, while gaining international recognition. At the same time, there was growing interest in the West for studies of Byzantine culture.

At this point, it is worth noting that Lord George Curzon, British Foreign Minister from 1919 to 1924, was a staunch supporter of the conversion of Hagia Sophia from a mosque to a museum. In fact, he himself raised it as a topic in the negotiations of the Peace Conference that ended World War I. However, he quickly backed down after meeting strong Turkish reactions to the possibility.

In August 1934, Whittemore’s team began work to restore the Hagia Sophia mosaics. On November 24, 1934, by an act of the Turkish Council of Ministers, the authenticity of which is disputed by some researchers, Hagia Sophia was declared a museum, and on February 1, 1935, it opened its gates with its new status.

However, according to the Kemalist conception, this new space had to highlight, among other things, the greatness of the Turkish nation. This unique architectural monument was included in the agenda of the Turkish leadership in the direction of the search for a new national history, which, however, could not leave out of the Byzantine period of Constantinople. Hagia Sophia has become an architectural symbol of the secularization and modernization of the erstwhile obsolete and backward, according to the Kemalists, Ottoman reality.