Kostas Pantelidis: From the Cuban crisis to the Kastellorizo crisis – Game Theory in the Mediterranean

27/07/2020

Greco-Turkish relations have entered a long-unseen state of tensions, reminiscent of an ominous past. Since the failed military coup against Erdogan, in July 2016, the country’s foreign policy and regional intervention have grown aggressive. This new assertiveness, largely due to the vacuum created by the withdrawal of the United States’ traditional role in the region, has strained relations with neighboring nations and traditional allies.

On 27 November 2019, Turkey signed a Memorandum with the Tripoli government, establishing their EEZs, without considering the islands of Rhodes, Karpathos, Kasos, and Crete,aiming at exploiting the hydrocarbon resources of the Eastern Mediterranean. That came as an answer to the trilateral agreement between Cyprus, Israel, and Greece forwarding the $6bn EastMed project.

The accord was deemed illegal by several countries and the EU as it infringes on the sovereign rights of Greece. The EU stated that the agreement does not comply with the Law of the Sea and cannot produce legal consequences for third States. On a Joint Declaration on 11 May 2020, Greece, Egypt, France, Cyprus, and the United Arab Emirates denounced the deal as it ignores the existence of the Greek islands. The elected Libyan parliament has also rejected the deal.

Athens has declared that any attempt to actualize the treaty with Turkish drilling missions in the region poses as a red line. After months of escalating tensions, on the 21st of July, the situation escalated. Ankara declared a NAVTEX on waters, 80-170 miles south of Kastellorizo, which lie under the Greek continental shelf-EEZ (according to the midline rule). Turkish warships and submarines moved towards that direction without the research ship Oruc Reis, however, which remains anchored in Atalaya until now.

The Greek armed forces immediately declared an alert and deployed 80% of their naval power. After a series of communications between Berlin and the two sides, the Turkish fleet halted its movement. According to the triumphant statement of the German agency Bild, Merkel’s intervention prevented a conflict (something that was later rejected). On July 22nd, Greece and Cyprus issued theirown NAVTEX over the same region as a counter.

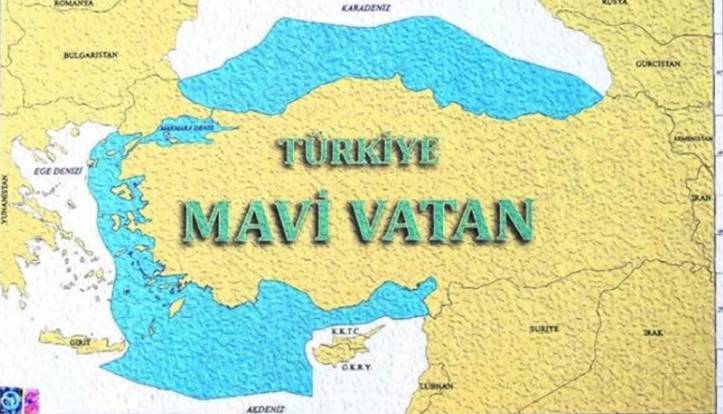

The German intervention helped to defuse the tension temporarily, but it didn’t diminish the ‘Blue Homeland’ doctrine. Simultaneously, the Turkish National Assembly, on the 22nd of July, reconfirmed the country’s decisiveness to protect their interests over the Eastern Mediterranean. In that sense, a revision of the 21st July events, with the American elections on the horizon, is probable. By using political game theory, modeling this emerging crisis to the paradigm of the Cuban crisis, we may examine the potential scenarios.

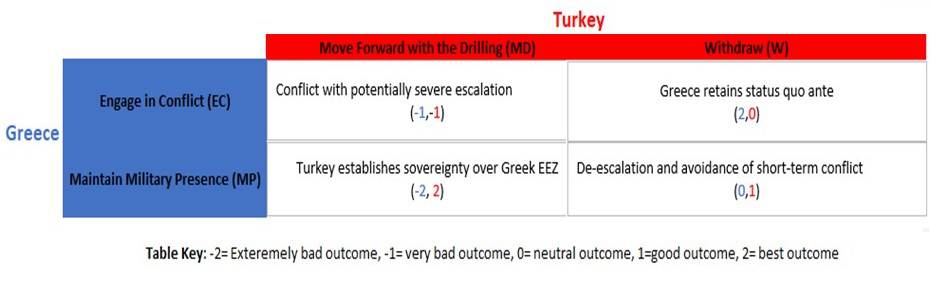

Scenario 1: Conflict with potentially severe escalation

A large-scale conflict would be the worst possible scenario for both sides. There is relative parity in naval forces and Greece, unlike Iraq, Syria, and Libya has an organized and well-equipped army. Both sides will certainly suffer catastrophic losses and this conflict will definitely create geopolitical shockwaves that will shape the balance of power and the Mediterranean future. Both countries are NATO allies. This will create the imperative for rigorous decision making by NATO, the EU, and the UN, paving the way for global power(s) intervention.

The outcome of such a scenario is ambiguous, to say the least, and we would have to examine each scenario individually. Certainly, both parties will be damaged, and the outcome will cause a major disruption of the regional status quo. A dangerous precedent will be set,and the region will destabilize.

Scenario 2: Turkey establishes sovereignty over Greek EEZ

In such a case the Turkish fleet advances and the Oruc Reis starts conducting its research while Greece simply maintains its military presence without intercepting.Then Turkey would have established de-facto sovereignty over the Greek EEZ with a fait accompli that will help enforce the Memorandum with Libya.In this scenario, Turkey turns the Eastern Mediterranean into a ‘Turkish lake’, effectively controlling the naval Sino-european trade, the hydrocarbons,and achieving an in-part materialization of the ‘Blue Homeland’ doctrine. A huge victory for Ergodan’s regime/

Greece on the other hand, losses more than 180.000km sea territory with the corresponding access to energy resources. The East Med project diminishes and Cyprus stops having continuity with the European space. Such an outcome would devaluate the geostrategic significance of Greece as the naval area stretching from the Adriatic Sea to Israel would have been severed.

This outcome would have a destabilizing function for Mitsotaki’s government. Greece’s trajectory would be en route to Finlandization. A reminder here is that Finlandization is the process by which one powerful country makes a smaller neighboring country abide by the former’s foreign policy rules while allowing it to keep its nominal independence.

Scenario 3: Greece retains thestatus quo ante

In this scenario, Greece advances to intercept the Turkish armada and Turkey withdraws. This scenario seems highly unlikely and it could only be an outcome of foreign interference. Turkey will suffer defeat, externally, and internally, with all that entails. Greece will project its ability to defend its legal rights. The status quo will remain as it is.Nonetheless, it is more than impossible that Erdogan’s Turkey will accept this outcome. Such successful crisis management by Athens will most probably lead the disputes on the continental shelf and the EEZ, to the ICJ or international arbitration.

Scenario 4: De-escalation and avoidance of the crisis scenario

In Scenario 4, both parties agree on de-escalation with timing playing a critical role. The two fleets abandon the territory. This can be achieved by foreign intermediation. The outcome would be a temporary de-escalation without losses from either side. In the aforementioned context that would be the best possible outcome collectively, unless the de-escalation occurred with terms for bilateral negotiations.

That would possibly benefit Ankara since Turkish claims -not just for the EEZ- would be legitimized. It is, thus, a scenario that offers Greece the short-term relief of avoiding military conflict, but behind it lies the long-term continuation of Turkish assertiveness. The Imia/Kardak events of January 1996, when two Greek island rocks transformed into de facto disputed soil following the crisis, should not be forgotten by Greek foreign policymakers.