Giorgos Iliopoulos: A Chinese memorandum for Tehran

13/08/2020

The effects of Saudi Arabia’s oil price war during the two months of March-April, combined with the pandemic, have ultimately benefited Beijing, which is also taking advantage of Russia’s strong presence in semi-autonomous Kurdish Iraq to sharply increase its influence in the disputed energy zone.

The prize for the Chinese and Russians in Iraq is of course of enormous value, although many in the energy industry do not realize that it is being underestimated, maybe even dramatically. Official figures for Iraq’s crude oil reserves are around 142.5 billion barrels (18% of Middle East reserves and 9% of global), making the country the second largest OPEC producer after Saudi Arabia.

The average cost to pump Iraqi oil from the ground is $ 2.15 per barrel according to the International Energy Agency (IEA) and is estimated to be fully competitive with the corresponding cost of Saudi Arabia ($ 3.00), while the corresponding cost of Iran is moving even lower, at $ 1.95 per barrel. Iran and Iraq put the final production cost at $ 9.09 and $ 10.57 per barrel, respectively, including capital expenditures, gross taxes, management costs and transportation costs.

In the natural gas sector, Iraqi reserves are estimated at 135 trillion cubic meters, bringing the country to the twelfth position in the world, although its known reserves are directly linked to the already exploited crude oil deposits.

But despite the periodic increases in estimated specific sizes, which remain extremely conservative compared to those of neighboring oil-producing countries, since much of Iraq’s subsoil remains unexplored, as opposed to other major crude oil and natural gas-producing countries who conduct very intense surveys.

232 billion barrels

The IEA data for Iraq comes mainly from the large and very important US Geological Survey (USGS) conducted in 2000, supplemented by data from subsequent upgrades. According to this estimate, the usable reserves of crude oil and liquefied natural gas reach 232 billion barrels.

According to a thorough stud by the PETROLOG group, this assessment is broadly confirmed. We note that the group is engaged in the provision of specialized services in the energy sector by conducting drilling, real-time analysis of geological data, analysis and evaluation of drilling samples, geophysical surveys and studies, design of mechanical equipment and project management.

But these estimates do not include data from the Kurdish zone in the north, nor do they address any major geological anomalies in central and western Iraq. However, even with these data, the country a decade ago had a production of 15% of its estimated reserves, when the average in the Middle East was during the same period at 23%.

At the same time, out of the 530 possible hydrocarbon deposits based on geological indications and prospects, only 113 have been explored, with favorable results for 73, ie a success rate of 65% and despite the fact that drilling is underway in some of the rest, new sites are added to existing ones based on new advanced means of analyzing seismic and historical data.

China’s wider strategy

The steps taken by Beijing not only have a financial background, but also reveal clear strategic aspirations. It was not until 2019 that the Chinese attempted to bring Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Emirates into their orbit of influence, without any success whatsoever.

However, they also discover in practice that it is impossible to maintain a strategic partner relationship with Iran and the Arabian Peninsula at the same time, so they concluded that their most important choice given the prevailing conditions is Tehran.

Beijing is aware that its vital need to secure access to the Persian Gulf and energy resources in that geographic area limits the ability of the United States to influence energy flows to China in the event of a crisis or war.

China imports more than 70% of the crude oil it consumes and 40% of that comes from the Persian Gulf. Its dealings with Iran, combined with its strategic alliances, in many ways bypass US attempts to punish the two countries’ leaders with heavy sanctions.

At a time when Tehran and Beijing are seriously threatened by US action against them, the new agreement offers real relief and increased strategic resilience. In fact, if Russia is added, given its decisive influence in the Middle East in this relationship, then the vital trade area is expanding dramatically with great benefits.

The real challenge

The real challenge for China, however, is focusing on managing the terrible economic crisis that is following the pandemic, which now ranks at level 5 compared to 2008, which merely reached level 3 (the relationship is defined on a logarithmic scale). In the volatile environment, the Chinese know that the Pakistan corridor is threatened by India and is in danger of being cut off at any time, even by Indian military intervention, creating terrible problems.

But the new agreement with Iran betrays that Beijing has already studied how to deal with this negative possibility and its possible effects on the ease of exploitation of the Indian Ocean maritime corridors, so the new corridor of Iran compensates for any difficulties.

Beijing’s alternative, however, winds up in the heart of Turkey, a country that is also suffering financially, spiraling in a catastrophic financial vortex desperately leading it in search of credit bailouts. With the Turkish president currently blocking his country’s access to the IMF, the new deal with Iran is an unexpected rescue model.

Despite strong objections in Iran to the fact that the burdensome terms of the Tehran deal actually mean the sale of the country at a bargain prices to Beijing, no one in Ankara has commented. Although Tehran’s co-operation with Moscow and the Iraqi Kurds in building an energy corridor to the west runs counter to Turkish interests, Beijing’s shadow has suddenly gained a special weight in the region and it has become virtually untouchable or unable to be circumvented.

Turkish fears

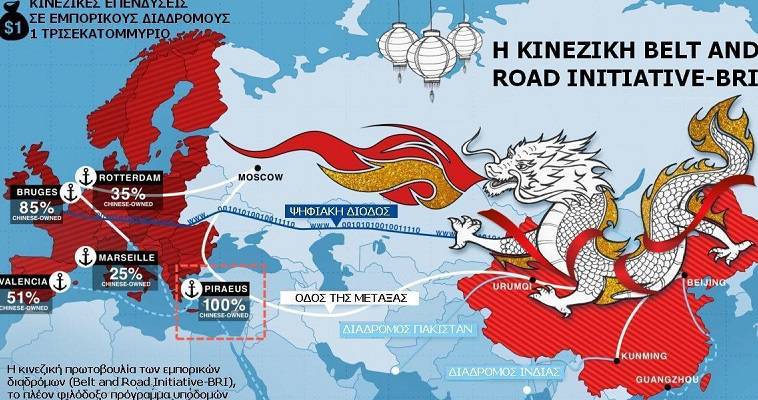

However, Turkey’s inclusion as a strategic partner in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), on the one hand, implies the acceptance of similar burdensome terms, such as Tehran, and at the same time the anger of the Americans. The Turkish regime realizes that such a possibility entails strong reactions inside the country where, as in Iran, the agreement will be treated in the form of an infamous sale, but also extremely severe sanctions by the US.

Ankara is probably aware that one of the conditions provoking popular outrage in Iran is Beijing’s complete control over the export of industrial goods from the country, but also the strict monitoring of the distribution of energy revenues in the right development directions, such as have been designed by Chinese experts. However, Ankara’s only hope is based on the launch of a Chinese initiative to start negotiations, in order to at least appease the furious markets with the expectation of some form of support for the Turkish economy from Beijing.

However, there is no serious prospect, in 2020, of preventing the path to bankruptcy and if we take into account that in the case of Tehran the Chinese have shown the necessary patience, so that the country due to its dire economic situation may exhaust its options, probably if and when they decide, they may do the same for Ankara.

On the other hand, the western world is dealing with the ubiquitous unrest in its region, worrying about the dangerous show it is giving to Libya and the Eastern Mediterranean, giving mainly to the Chinese and secondly to the Russians the opportunity to quietly complete a enormous geopolitical change in Central Asia and Mesopotamia.