Giannis Theocharis: Evidence of the indifference and destruction of Byzantine monuments in Turkey

15/09/2020

The decisions to convert the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul and the katholikon of the Monastery of Chora into mosques constitutes the culmination of a tendency to remove monuments from the General Directorate of Archaeological Sites and Museums and return them to the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet). This trend concerning Byzantine monuments began in 2006, when Hagia Sophia of Vizyi was turned into a mosque.

During Erdogan’s rule in Turkey, especially with the purges that followed the 2016 coup, the Directorate of Religious Affairs became an organ of the Justice and Development Party. The same happened with the Council of State, which annulled the old ministerial decisions on the use of mosques as monuments.

Unfortunately, things will not stop here. The view expressed by the academic Ebubekir Sofuoglu that idols (ie the soulful Byzantine depictions) and the Byzantine Empress Zoe (due to her three marriages) have no place in Hagia Sophia is worrying.

It is unknown whether the iconoclastic actions of the Turks are limited to covering Byzantine representations. It is completely unlikely that a representative of the Archaeological Service will participate in the new management body of these monuments, so that their protection is a priority.

In addition, there are dangers for other Byzantine monuments of the city. The first of these is the katholikon of the Studion Monastery (Imrahor Camii). This is a ruined inaccessible monument that was left to its fate for years, which was claimed in 2013 by the Diyanet from the Archaeological Service, in order to rebuild it and make it a mosque again.

Not even one organized archeological site

The second monument is the katholikon of the Monastery of Pammakaristos (Fetiye Camii), a monument to which a mixed regime of use is applied: the church functions as a mosque and its chapel with the mosaics as a visitable monument (museum). Like most of the Byzantine monuments of the city, Pammakaristos is located in Fatih, the center of the Islamic fundamentalism that is developing in the city.

Turkey’s general policy on archeological heritage has always suffered. It is noteworthy that there is no organized archeological site in all of Istanbul. The Museum of Mosaics is a place that in no way highlights the historical identity of the Grand Palace, ie the complex from which the exhibited mosaics come.

The excavated area of Agios Polyefktos (a very important ruin) is an open vineyard, the Byzantine walls are an area that hosts people in the margins of society, while other Byzantine ruins, such as the church of Agios Karpos and Papylos in Psamathios, belong to private owners who ask for money to visit them.

Any sensitivity to monuments in Turkey has always been manifested only in the context of the country’s approach to Western standards. This tradition was started by the pioneer archaeologist Hamdi Bey in the late 19th century, strengthened with the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923, but in recent years has waned. In 2011, Turkey began to demand in every way from Western countries the return of cultural goods that had been exported from its territory, while at the same time restricting the activity of foreign archaeological missions within its territory.

The culture of “It’s mine”

In Turkey, antiquities are considered solely in the light of ownership, following the position that the country is an area that came under the occupation of the current inhabitants after victorious wars. For Turkish antiquities only the meum esse (“it’s mine”) applies, in a way reminiscent of the reasoning of a Japanese businessman who had bought a portrait of Dr. Gachet by Van Gogh, and wanted to burn with him so that his children could avoid inheritance taxes. Monuments in Turkey are not protected as such, simply because their historical and artistic value is not recognized as such.

Thus, the archaeological landscape in Turkey is not directly comparable to that of the Mediterranean countries of Europe (Italy or even Greece) in terms of the institutional framework of protection. The fate of antiquities in Turkey has deteriorated in recent decades due to Erdogan’s neoliberalism, the only Western line that the ruling party has consistently followed.

If in Greece we are concerned with the installation of wind turbines in the natural and archaeological landscape (see eg the Valley of the Muses in Boeotia), in Turkey this form of investment invaded without any problem the monastery of St. Symeon the Miraculous (Asiz Simon manastir) near in ancient Antioch on Orontos.

A whole spa town was lost

In the present-day province of Izmir, the ancient spa town of Alliani was lost in 2011 in the waters of the Yortanli dam, despite calls from international organizations. At the Yenikapi in Istanbul, the much-publicized rescue excavation at te Port of Theodosius, archeological work was completed with Erdogan’s personal intervention to complete the Marmara Tunnel. Even in Zeugma, the ancient city next to the Euphrates, the losses are not negligible: 80% of the city is under the waters of a dam, without the rescue excavations being completed, while people admire what was removed from the mosaics which are exhibited in Gaziantep.

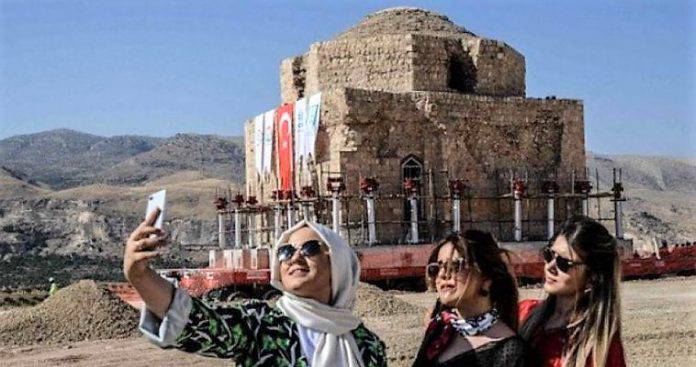

There are many examples of the destruction of antiquities in Turkey due to infrastructure projects. Most of all, however, what stands out as an act of barbarism towards a significant archeological site is Hasankeyf in southeastern Turkey. Hasankeyf, one of the oldest settlements in the world and one of the best preserved medieval settlements in Turkey, developed in an idyllic landscape near the Tigris riverbed.

Already in April, it began to be covered by water due to the Ilisu Dam, despite international calls and mobilizations, which led in 2009 to the withdrawal of Western banks from financing the project.

In Greece this news did not touch many, even in the archaeological community itself. But, our neighbors should concern us more and in a meaningful way, as Greece and Turkey are heirs of cultures that developed in the Mediterranean, the material remnants of which the two countries seem to manage from different points of view. Is that true, though? By and large, yes. But in rare cases, probably not.

A similar case in Thessaloniki

In Hasankeyf, the Turkish state implemented the following plan as a minimum example of protection of the antiquities there: in 2017 and 2018, some monuments were removed from the site and moved to an adjacent archeological park. In 2013, something similar happened in Thessaloniki: a ministerial decision was issued for the dismantling of the Byzantine crossroads located in Venizelou and its transfer a few kilometers away to the Pavlos Melas military grounds.

However, the reactions of scientists and citizens prevented the implementation of the 2013 decision, led to another in 2017 to keep the space as it is, which was again abolished this year with another problematic proposal, which is aptly compared to Dr. Frankenstein’s experiment. It remains to be seen whether Greece will meet Turkey at the Byzantine crossroads of Venizelos, agreeing with it on the oriental ways of settling outstanding issues arising from our fatal contact with the past.