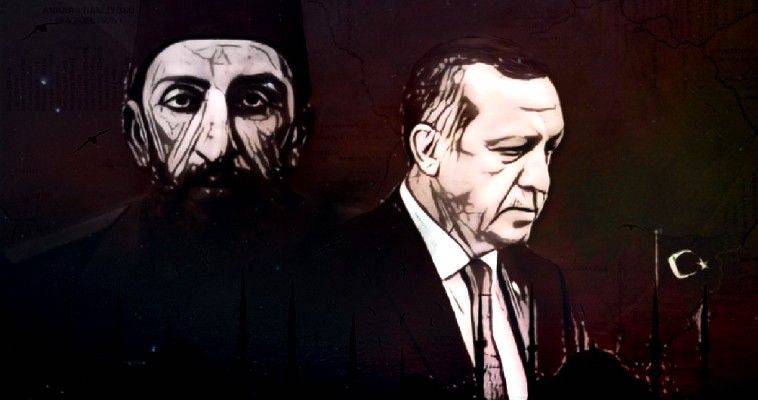

Vlassis Agtzidis: Erdogan’s roots in Abdulhamid and the Young Turks

06/07/2020

Turkey is going through a period of gigantic transformation at all levels. With the initiatives in Erdogan’s hands, Turkey is on a new path. These new venues, when they first emerged as a liberal prospect with the defeat of the Kemalists, were promising for the perennial have-nots of this cruel state. But things have changed in the political arena since the start of the 2013 Islamic civil war.

The confrontation with Fethullah Gulen, Erdogan ‘s former ally, led the Turkish president into an alliance with his old enemies. All imprisoned military officers, as well as non-military personnel involved in the famous Ergenekon and coup d’état organization (Balyoz Harekâtı, which was organized in 2003 against the government of the Justice and Development Party), were released in 2014.

These will now be Erdogan’s new allies in the war waged against Imam Fethullah Gulen’s movement. The new nationalist activists who drew inspiration from the genocidal Young Turk Talaat Pasha were joined by Bahceli’s far-right Nationalist Movement, also known as the Gray Wolves, as Erdogan’s allies.

After 2014, the Kemalist nationalists of the deep state returned to Turkish reality. As Cengiz Candar writes in his text “New Turkey: Neo-nationalism or the reincarnation of the ‘Old’?”, they were not only released from prison, but in many cases returned to their central positions in state security services.

Candar believes that these nationalist circles (also called Eurasianists), which are strong in the armed forces, have drawn up a rapprochement between Turkey and Russia that began on the eve of the failed 2016 coup, which took place as a result of this approach. What is happening is that the old Kemalist deep state is now occupied by anti-American and anti-NATO perceptions. It supports a reorientation strategy for the east that would make Turkey a partner of Russia, Iran, and China.

The pro-Western coup

In 2015, the coalition formed between Erdogan and the nationalists in 2014 was expanded with the participation of Bahceli’s far-right party. The military coup of 2016, which had a pro-Western tinge and tried to prevent Turkey’s cessation from the Western framework, further consolidated Erdogan’s alliance with his new friends.

The orientation of the failed coup may interpret Greece’s incomprehensible attitude to support it morally, giving political asylum to coup plotters. It is already clear that certain circles – perhaps linked to the international centers that instigated the coup – have been dynamically activated, taking advantage of the tolerance and leeway of a Western-style semi-decrepit Republic.

They managed to mobilize a portion of public opinion on the basis of the “human rights” of the coup plotters and ultimately managed to influence Justice, which gave political asylum against the will of the then Greek government of AlexisTsipras and mainly against objective Greek interests.

The roots of the “New Turkey”

Cengiz Candar admits that “a closer look reveals that secularists and Islamists are in fact two sides of the same coin.” He writes: “Since 2015, Turkey has been governed by a nationalist coalition that is an amalgam of neo-unionists [Kemalists who draw their inspiration from the Young Turk figurehead Talaat Pasha], traditional ethnic right-wing nationalists and Islamist nationalists. It has been further cemented after the 2016 coup attempt. It is, in a sense, a continuation of “Old Turkey”, which had its roots in the last days of the Ottoman Empire.

It is a coalition that revives and joins together two distinct traditions: the secular nationalism of the Young Turks, the unionists, and the Islamism of Sultan Abdulhamid II. Abdulhamid was a despot who sought to maintain the unity of the Ottoman Empire by emphasizing an Islamic identity at the expense of the Christian subjects. The Young Turks were secular nationalists, but in fact, after 1909, they finished what Abdulhamid had begun when they annihilated the Ottoman Armenians.

“President Erdogan is seen as the reincarnation of Amdulhamid by his Islamist supporters, the sultan who is despised for his Islamism by secularist nationalists, in the unionist and Kemalist tradition. Yet in an ironic twist, Erdogan recently – and for the first time – embraced the secular founding father of Turkey, Kemal Ataturk, to the consternation and astonishment of some in his own constituency. But that was no coincidence. ”

The conclusion is that the roots of Erdogan’s New Turkey can be traced back to the last period of the Ottoman Empire, and to the supranationalist policy of the Young Turks. New Turkey is being built through the descendants of the Young Turks who formed as a distinct political trend in modern Turkey (Candar calls them “neounionists”) and their alliance with Erdogan.

The positive image of the YoungTurks in Greece

Let us just remember that the Young Turks (Committee for Union and Progress) were the ones who organized and carried out the genocides of the Christian communities (Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians). And it was later that in the newly built Turkish Republic they created the so-called deep state, which has been maintained, through mutations, to this day.

The concept of a state within the state emerged in Turkey in the last days of the Ottoman Empire, when the Young Turks formed the Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa (Special Organization) parastatal organization. It undertook the extermination of Christian communities in the midst of World War I and then pioneered the creation of new structures in the Kemalist state.

Knowing, then, what the Young Turks were and what is important today, understanding the tradition of the Young Turks is necessary in order to fully comprehend the history in our region, but also the modern trends within Turkey. It is clear that a rather positive image of the Young Turks has prevailed in Greece. Even reputable historians have expressed anti-historical views on the phenomenon.

Characteristic was the article by Antonis Liakos “Does Greece have ‘Young Turks’?”. Mr. Liakos’ extremely positive image of the Young Turks provoked some interesting texts that challenged it, such as that of Irida Tzachili, “Commentary on the Young Turks in the article by Antonis Liakos”, or Alexandra Deligiorgi’s “Historical Science and historical memory, and poliy. On the genocide of the Pontians”. My contribution to the deconstruction of Mr. Liakos’ positions was: “What Young Turks? An Issue Still Unclear”, the publication of which was denied by chronosmag.eu.