Vaggelis Georgiou: Greek delusions in 1976 about Turkish aggression

28/11/2020

If we take a look at the statistical ‘progress’ of violations in the Aegean by Turkish Armed Forces, we should be very worried. According to the data of Hellenic Armed Forces General Staff (GEETHA) (see table), the Turkish aggression in less than six months (2019) has penetrated the Greek borders many times more than in the past.

Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar has even stated that “we have the power to conduct a military operation in Afrin and at the same time in the Aegean”. At the same time, the Turkish economy is getting from bad to worse, despite temporary stabilization. Does the crisis looming over Turkey affect Erdogan’s aggression? This is what Athens believed in the 1970s about the aggression of the then Turkish governments!

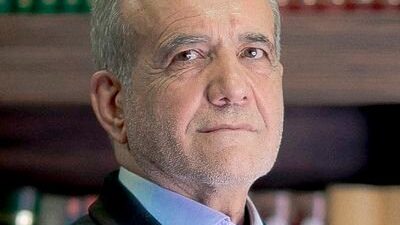

In the 1970s, the successive Karamanlis governments had set their sights on joining the EEC. By setting their sights on this redemptive, as they believed, political act, Panagis Papaligouras was assigned the most important portfolios, that for Coordination and Planning, and that of Foreign Affairs (1974-1978). He was a first-class politician whom Konstantinos Karamanlis has trusted with ministries since the 1950s.

In September 1976, in an interview with Times journalist Mario Modiano, the minister stated: “None of the Greek-Turkish differences are economic or social. Greece has no reason to compete with Turkey in these areas as the per capita income is many times that of Turkey. We will never put obstacles in the way of any measures taken by the EEC member states that favor Turkey. It was in Greece’s interests because in that way, the Turkish aggression towards Greece might have been reduced.” The Greek minister referred to the economy in this way so as to explain how the Greek-Turkish conflict can even be resolved!

The Greek proposal on the Cyprus issue

At the same time, the powerful man of Greek diplomacy, Vyron Theodoropoulos, had told a European official on the Cyprus issue: “if the Turks prove that the problem is economic and not territorial, solutions are always possible.” Greek leaders devised an “original” way to get Turkey to withdraw its troops from occupied Cyprus.

So they asked the Europeans to convince the Turks that they would improve their economic situation if they reduced their military spending and withdrew the costly occupation troops from the island. The problem with this logic, however, was not only its distance from reality, as was subsequently proven by the facts, but also that “no one in the EEC approached the problem in this light,” as a German Foreign Ministry official had jokingly said at the time.

On the contrary, Brussels admitted that they were wrong (!) not having helped Turkey financially, as the then President of the Commission François-Xavier Ortoli had told Papaligouras. In other words, the diplomats of Konstantinos Karamanlis steeped in delusion saw their hopes dashed. The most important thing, however, is that Turkey itself was of a completely different mind.

Turkish finances

Both the naive Papaligouras and his European interlocutors tried to find formulas to help the Turkish economy in order to make the neighboring country less aggressive, Turkey was shaping another reality. The link between state aggression and low per capita income is not a baseless theory. However, in the case of Turkey, it does not work. And we will see why. If we correlate the numbers with the people we see that the living standard of the Turks has skyrocketed since the 1970s.

According to the World Bank, Turkey has made impressive progress in GDP per capita growth among 195 countries. While in the 1980s one in two Turks was long-term unemployed, today the rate has dropped to 21%, according to OECD figures. According to a study by Amikam Nachmani, in the period 1965-1998 Turkey was ranked as the 7th fastest growing economy among 30 countries. Its GDP has quadrupled and its per capita income has tripled.

Logically, then, according to the Greek logic of the 1970s – there should be mitigation of Turkish aggression. However, in the 1980s Turkey spent 20.3% of GDP on its military, while Greece spent 10.5%. In 2014 it dropped to 6.4% (Greece to 4.8%) according to SIPRI data.

Did anything change Probably not? The two countries, let us recall, were on the brink of war in 1987 and 1996, while throughout 2020 the thermometer in bilateral relations is in the red. The first table shows the large number of Turkish violations despite the fact that the standard of living of the Turks was at its best. 2019, an extremely difficult year for the Turkish economy, is also full of record violations.

As Lieutenant General Hippocrates Daskalakis had told me, “the tendency to avoid military adventures appears when peoples have high living standards and when the available means make resorting to conflicts counterproductive, while the national interests are better served by other methods. Turkey is closer to that expansive point where a thriving new bourgeoisie with a surplus of young people is vulnerable to adventure.”

The relevant indicators do not confirm Papaligouras’ perception. In fact, this perception – says Daskalakis – is “similar to the refuted perception of the reduction of friction with the removal of the military establishment and the restoration of democracy, as the increase in per capita income is accompanied by an increase in aggressive entanglements and revisionist aspirations.”

The rampant fascism of the Turks

Various romantic/idealistic attempts to highlight the role of citizens in the normalization of Greek-Turkish relations have fallen on deaf ears. At times a large part of Turkish society resisted authoritarian regimes (riots of the 1970s, Gezi 2013, etc.), but unfortunately, there has been perpetual oppression of the state over civic society.

In the 2016 referendum, the Turks gave Erdogan a majority, albeit slight, and made him a powerful president. The words of sociologist Cihan Tuğal sound disturbing. Tuğal speaks of the “progressive fascism” of Turkish society in recent years.

A relatively recent poll found that more than 60% of Turks wanted the country to buy the S-400s from Russia. “Turks know what war really means,” wrote journalist Barcin Yinananc in 2018. “First Iraq, then Syria, Turkey has been in a war zone for more than two decades. Greeks should appreciate that it is a blessing to be relatively far from a War zone”.

Over time, authoritarianism has withstood any reform effort, from inside the family to schools and from the military to politics,. Even the late Turkish journalist Mehmet Ali Birand admitted it. As early as the 1950s, an Israeli diplomat stated in a report that “above all, Turks respect power, and the more brutally it is expressed, the more they like, appreciate, and understand it.”

For Greece, however, the problem begins when this authoritarianism passes into the foreign policy of the neighboring country, demonstrating that it has an independent function and unaffected by economic indicators. The son of the late Papaligouras and later also a minister of ND Anastasios Papaligouras “suspected” that his father “considered the economy a very serious matter to be left to economists alone”. We would add what his father, who wagered so much on Greece’s accession to the EEC, did not understand: a good economy may have filled the Turks’ kettle, but it did not quench their expansionist appetite.