Stavros Lygeros: Why Turkey is lost to the West – The neo-Ottoman revolution is not a parenthesis

25/11/2020

After 18 years in power, Erdogan has radically changed Turkey. In this sense, what happened in the neighboring country is a real revolution, even if the way it was done differs qualitatively from the classic revolutions of the 20th century. The fact that Western leaders are usually blind does not mean that this is not the case.

But how is it possible that the ideological point of view and the personal political interest of a leader can bring about such a major shift in the geopolitical orientation of a country? After decades of attachment to the West, which shaped perceptions, influences and interests, why was there no strong resistance from the traditional ruling elites there?

The question is crucial and to answer it two factors must be taken into account. The first is the traditional relationship of the Turkish economic elite with political power, combined with the atrophic “civil society” in Turkey. The second is the tectonic changes that have taken place since 2002, when the Justice and Development Party won elections and formed a government.

The enterpreneurial class

Both in the Ottoman Empire and later in the Turkish Republic, big business had little political influence compared to the West. In both periods, political power had the upper hand because it controlled the state. In the Ottoman period it was the sultan, who institutionally had absolute power over his subjects, regardless of the wealth they possessed.

After the proclamation of the Republic in 1923, political power was held – in the context of an authoritarian regime characterized by intense statehood – by the Kemalist military group that led the war and the establishment of the nation-state, which succeeded the empire. Entrepreneurs of the time did not have the opportunity to claim a share of influence. They were, after all, relatively weak. This did not change much after the war, when, in order to adapt to Western standards, Turkey adopted a multi-party system.

Gradually, large business groups with a large economic and social footprint developed in Turkey. In their entanglement with the political elite, however, they never managed to get the upper hand. That has not changed in the years that the Justice and Development Party has ruled. Much more so when Erdogan set up his own regime. In fact, he made sure to exterminate in an emblematic way a big businessman-media mogul who had stood in his way, just to send the message to everyone.

Erdogan as the “favorite child” of the West

Initially, Erdogan was the “favorite child” of the West. He gradually became a problem when he began to unfold his own agenda for the role of Turkey. It seemed then that he wanted did not want to be the ultimate link in the Western security system, nor the “bridge” of the West to the Muslim world, as the Obama administration and the European capitals imagined. It then appeared that Erdogan wanted Turkey as an autonomous regional power to play a game for itself.

Erdogan has unfolded his agenda since 2012, after his final victory in the ten-year informal war with the post-Kemal “deep state”. When the Americans realized the tendency of his geostrategic autonomy, they sent him the threatening message with the corruption investigation carried out by the Gulen network controlled by them in the mechanisms of the Turkish state.

But instead of rushing to bow down and adjust, Erdogan declared war and began dismantling the Gulen network, and under that pretext all Western networks that peddled American and European influence in Turkey. Thus we reached the failed coup of 2016, which provided the legal basis for mass liquidations across the range of state mechanisms and beyond.

To dismantle American and European networks of influence, Erdogan played a strong role not only in the plot of the Gulen conspiracy, but also in the deep-rooted history of Turkish society that the West was plotting to mutilate Turkey. He cultivated this narrative, citing US support for the Kurds in Syria as proof that the creation of a Kurdish state is under way.

Erdogan’s power complex

The result of all this, and especially of the failed coup, was also that Turkey was led to a second coup. The first was the ten-year transition from the post-Kemalist to the neo-Ottoman regime. The second was the transformation of the neo-Ottoman regime into a regime dominated by Erdogan’s personality and surrounded by anti-Western forces in Turkey.

The post-Kemalist regime was collectively dominated by a political-state elite, framed by an economic-social elite. In the neo-Ottoman current, Erdogan was the leader, but he co-ruled a leading group and informally with the Gulen network. Today the ruling Justice and Development Party is very different from what it was 10-15 years ago.

Leaders have been marginalized, while others, such as e.g. Gul, Babacan, and Davutoglu have turned against Erdogan. They do not unreasonably believe that moving away from the West will have negative consequences for Turkey. This concern is shared by many in the country’s traditional ruling elites, but they are powerless to influence things, fearing that they will be accused of being part of Gulen’s “conspiracy”.

Erdogan, then, has gone from being the leader of a current to an informal monarch, to an elected neo-sultan. It is indicative that as a rule he is surrounded not by the old guard of his party executives, but by relatives and submissives, as well as by executives of the traditional “deep state”, who are carriers of anti-Western ideology.

Turkey is lost to the West

This practically means that Turkish national interests are not defined and understood collectively by a ruling elite, but by the neo-sultan and his court. In other words, Erdogan’s personal interest is in Turkey’s national interest. He is convinced that if he returns to the western “fold” he will be taken hostage. The American networks of influence will be reconstituted and will probably be used to bring about its deconstruction.

In this way, it adds a broader ideological and political dimension to the current rift, which is barely covered by its peculiar and, for many, politically inexplicable relationship with the outgoing President Trump. The contrast is no longer between the American “deep state” and Erdogan. It is not unidimensional politics. It is cultural at the same time. It is between the West and “deep Turkey”, even if Westerners, with the exception of President Macron, refuse to realize it.

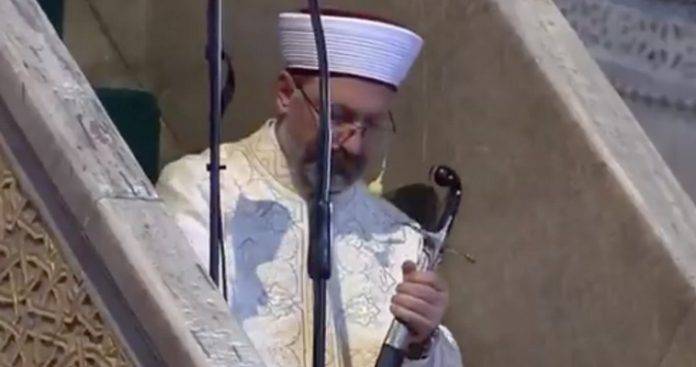

This was clear in the case of Hagia Sophia. The conversion of the historical monument into a mosque and the whole ceremony of the first Muslim prayer with the sword in the hands of the imam refer to a symbolic revival of the religious wars: on the one hand Islam and on the other the Christian West. The same thing happened with the attacks of Islamic terrorism in France, which led its president to post the sketches of Charlie Hebdo in public buildings.

Erdogan’s neo-Ottomanism, as an ideology and political movement, is not only intended to close the historical parenthesis of Kemalism and reconnect Turkey with its Ottoman past. He also came with the ambition to turn Turkey into a leader of the Muslim world in an unspoken but clear anti-Western direction.

So the economic crisis may have tarnished Erdogan’s image, but his ideological narrative continues to move “deep Turkey”. And that will not change radically even if the political deterioration of the Turkish president intensifies. In fact, Turkey, at least as long as Erdogan is at the helm, is already lost to the West. And because it has been lost not only politically, but deeper, on the cultural level, it is unlikely to return to the Western “fold even in the post-Erdogan era.